Metrication status and history

In the 1970s, most British Commonwealth nations changed from the Imperial system of units to the metric system. Several of these nations rapidly and successfully made the metric transition, thanks to strong government encouragement and support. In addition, other countries have also made the change.

The chart (below) shows the chronology of the advance of metric usage around the world.

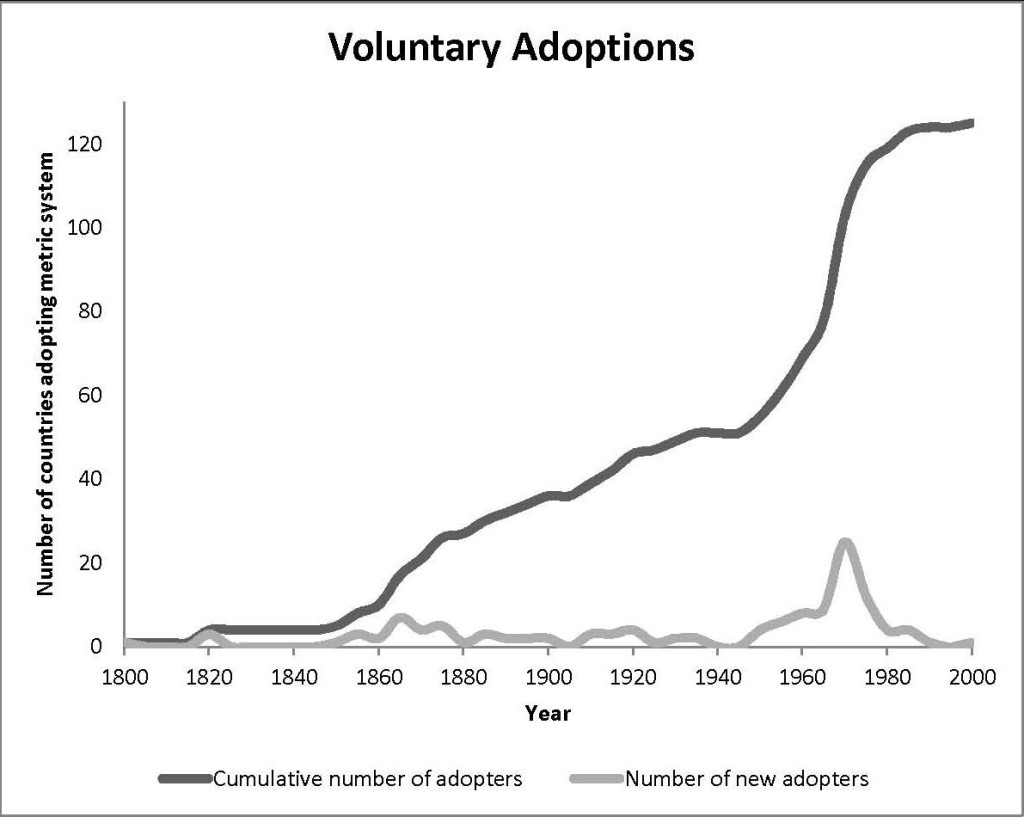

A second chart (below) from Hector Vera shows the number of countries adopted the metric system.

In addition, more detailed summaries of the the metric transition for the following countries are provided (below):

Advance of metric usage in the world

The chart (below) shows when various countries adopted the metric system and is based on a survey conducted by USMA many years ago. The chart shows the countries’ names at the time; some have since changed names. And, because metrication is an evolutionary process that takes place over time, any attempt to assign a single year to a country’s conversion is only an approximation. Outside of what is shown on the chart (below) most other details of that survey have been lost. However, since the original development of the chart, the information on Jamaica has been added.

- Only a few small countries, including some un-listed Caribbean nations heavily influenced by the U.S., have not formally adopted the use of SI.

- Among countries not claiming to be metric, the U.S. is the only significant holdout.

Number of countries that have adopted the metric system

A second chart and a table from Hector Vera (below) show the number of countries that have voluntarily adopted the metric system, both by year and cumulative.

Metrication in Mexico

By Hector Vera

The decimal metric system of weights and measures was officially adopted in Mexico on 15 March 1857. Until then, people in Mexico had used hundreds of measures that came from Medieval Europe, the Islamic culture, and pre-Columbian civilizations. These measures coexisted from the 16th to the 19th centuries in a metrological melting pot formed in the three centuries of Spanish colonial domination. Eventually, those measures were replaced by the metric ones, but not immediately. As was the case in many other countries, for decades the official adoption of the meter actually meant very little—if anything—to lay people. Actually, in Mexico, meters, liters, and kilograms were not seen in markets and homes until the 1890s.

The measures employed in the New Spain and during the first few decades of independent Mexico were inexact, poorly standardized, and often used only at a local level. Every city and every guild had its own standards and its own inspectors of weights and measures. Different sets of measures were utilized for different products: wine barrels varied from those of oil, dry measures (such as fanegas and arrobas) for corn were not identical to those used for beans, the units to weigh gold were not the same units used to weigh silver, and so forth.

The variety of local measures complicated commerce, science, and taxation, and growing demands for metrological unification, exactness, and standardization arose among scientists, large-scale merchants, and government agents. In the 1840s the Mexican Society of Geography and Statistics (Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística) prepared a report on weights and measures that recommended—not without heated debates among the members of the scientific community—the adoption of the decimal metric system as the only official system of weights and measures in Mexico.

But it wasn’t until 1857, after liberals controlled the government and undertook numerous modernization reforms, that the suggestion of adopting the metric system was finally accepted. The new legal disposition stipulated that by 1 January 1862, only metric measures could be used in commerce and legal contracts; all non-metric measures should be destroyed, and those who failed to obey the new law would be fined. The same law also implemented the decimal system of currency for the Mexican peso. A National Bureau of Weights and Measures (Dirección General de Pesos y Medidas) was created to design and carry out policies to disseminate the new decimal weights, measures, and money.

But despite the Mexican government’s best intentions to metricate the country, the metrological customs of the people remained intact. The government had an extremely problematical task. There were at least four big challenges for the Mexican state in this matter:

• To enforce the new metric legislation: A large number of well-trained inspectors and local offices of weights and measures was required.

• To teach the population how to use the metric system: Names and magnitudes of the metric units were completely unknown to lay people, and their decimal character was an arithmetic oddity; most pre-metric measures in Mexico used duodecimal, hexadecimal, and vigesimal systems that have greater divisibility than the decimal system. This required a large education system that did not exist at the time.

• To persuade people to use the metric system: In addition to teaching the metric system, the state needed to persuade people that the metric system was more useful than the old measures. A convincing ideological campaign was needed.

• To provide measuring instruments: It was necessary to import or build metric measuring and weighing instruments for commerce and government agencies (stores, workshops, mines, customs, etc.). With the new law, millions of measuring tools and implements would become obsolete and illegal, and millions of replacements had to be provided.

These were complicated and expensive matters. The vast majority of the population was illiterate, and there were no factories in the country to produce metric instruments, nor were there technicians to calibrate the existing tools nor inspectors to verify that merchants weren’t taking advantage of buyers. The government lacked the economic and human resources to carry out such a big enterprise. To make things worse, the country was entering a long period of social and political instability due to a civil war and a foreign invasion.

It was in the last decade of the 19th century, in the middle of the 30-year presidency of Porfirio Díaz, when political stability and economic growth created the conditions needed for an effective introduction of the metric system. In addition, the unification of weights and measures was a pressing necessity. The increasingly economic exchange with other nations and the economic integration of different regions within the country required a standard way to measure and value commodities that were consumed in distant places.

The Díaz administration was more effective than its predecessors in enforcing the law and had a better organized and financed bureaucratic apparatus. Growing networks of telegraph and railway systems made it easier for the National Bureau of Weights and Measures to coordinate its activities with local governments and to monitor the progress of metrication. Communication with governors was now quicker and more consistent, and inspectors and technicians could travel from Mexico City to the provinces faster than before. The arm of the law became longer and longer; it was much more difficult to ignore the legal requirement for using the metric system than in previous decades.

At the same time, international use of the metric system had significantly increased. By then almost all of continental Europe and Latin America had adopted it, and there were serious plans to do so in the United States. The Díaz regime was very interested in connecting Mexico with the “most advanced countries of the world,” and the introduction of the metric system was seen as a way to enhance commercial and intellectual exchanges with those nations—as well as an instrument to “civilize” Mexico.

These ideas gained force in the First International Conference of American States, held in Washington in 1889–1890. Among the topics discussed were the foundation of an American Customs Union; improving communication among the countries on the continent; the adoption of a common silver coin; laws to protect copyrights; and the adoption of a common system of weights and measures, i.e., the metric system. A single, global market was emerging, where manufactured products became more and more important in comparison with raw materials. This required an international system of measures to produce standardized commodities that fit the technical requirements of both producer countries and consumer countries. That year (1890), the Mexican government took actions to incorporate Mexico among the members of the Meter Convention, and to buy standards of the meter and kilogram from the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in Paris.

In 1895 the Congress passed a new Weights and Measures Act. With the new legislation, the government launched a national campaign to promote the use of metric measures. Brochures and handouts were widely distributed. These printed materials were both pedagogical, showing the rudiments of the metric system, and ideological, stressing that use of metric measures was a symbol of progress and civilization. The campaign was effective among urban populations, but in rural areas, where the majority of the population lived, people continued to use traditional measures.

New social disturbances—the revolution of 1910–1917—stopped the metric campaign. In 1917, as part of a reform in the Ministry of Development, the National Bureau of Weights and Measures was closed and the efforts to continue spreading the use of the metric system ended. As a result, people in small towns and indigenous communities did not learn how to use metric measures.

The government made no further progress in the metrication process until the 1930s, when the Ministry of Economy conducted a census of measures. The census showed that people in the countryside did not use metric units to measure their land or to weigh grain and other products. Peasants and farmers instead used more than 200 pre-metric units of measurement. To eradicate those vestiges of ancient measures, a new national metric campaign was launched during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940). The campaign targeted rural and popular classes, and disseminated more accessible materials than in previous campaigns.

Combined with an increasing access to formal education, where teaching of the metric system was mandatory, this campaign succeeded in turning the metric system into the most widely used system of measurement in the country. Today, some pre-metric units can be found in remote areas, and due to the influence of the American economy on Mexico, inch-pound units are used in some industries. But these are minor exceptions; the metric system is the prevailing system in everyday life, commerce, and industry.

In 1992 the Federal Government created a new central agency of weights and measures: the National Center of Metrology (Centro Nacional de Metrología). The center holds the national standards and carries out scientific and technical research in metrology.

Canadian Metrication

by Joseph B. Reid, President Emeritus, Canadian Metric Association

The use of the metric system for all purposes has been legal in Canada since 1873, but in fact only the scientific community used it until 1970 because its use was purely voluntary. It was only after the adoption of resolutions favoring metrication by associations of scientists, engineers, manufacturers and builders, that the government in January 1970 announced in a “white paper” that Canada would go metric.

In 1971 the government appointed Metric Commission Canada with the mandate of planning and managing the conversion. The Commission adopted the target of converting by 1980 every aspect of national life. Some hundred sectorial committees, representing all aspects of the national life, were named and charged with drawing up plans. To coordinate it all, every plan was entered in a critical path data base, with every plan ending at or before 1980.

Unfortunately, there was little correlation between the forecasts of a plan and its results. Government services, electricity, gas, water, engineering, medicine, the grain trade, and commercial and industrial construction all converted in good order. But house construction has remained solidly wedded to feet and inches, despite the conversion of bricks, concrete blocks, and bituminous tiles. Although lumber is still in imperial sizes, plywood thicknesses are in millimetres.

In all Canadian schools, colleges and universities for the last 20 years SI (the International System of Units) has been taught, and nowhere is the imperial system formally taught. In contrast, at home parents speak imperial. The result is that children state their “weight” (mass) in pounds and their height in feet and inches, all the while not knowing how many ounces are in a pound or feet in a mile.

Since 1976 the law requires that all prepacked food products must declare their mass or their volume in metric units. Milk has been thoroughly metric since 1980. Since 1984 95% of retail food scales have been converted to kilograms after a well planned conversion program in 1982 and 1983. However, a new Conservative government elected in 1984 halted all government promotion of the metric system. The result is that the price of bulk retail food is still universally posted in pounds with the kilogram price in much smaller type, even though the weighing at the cash register is done in kilograms.

Tooth paste was the first consumable to change, in 1974. On 1 April 1975 Fahrenheit temperatures were replaced by Celsius. (An opinion poll in 1989 found that 79% of the population thought in Celsius.) In September 1975 rain started to fall in millimetres and snow in centimetres. From 1 April 1976, wind speed, visibility, and atmospheric pressure have been in SI units, with the pressure in kilopascals. During the Labor Day weekend in 1977 every speed limit sign in the country was changed from mph to km/h. From the same time every new car sold had to have a speedometer that showed speed in km/h and distance in km. The distances on road signs were changed to kilometres during the next few months. Gasoline pumps changed from imperial gallons to litres in 1979.

Since the old metric system was almost unknown in Canada, SI (the International System) was adopted almost without discussion. It is worth noting that the kilogram-force and the bar are not used. On the other hand, dieticians still use kilocalories, and doctors use millimetres of mercury. As for the quart, the pint and the ounce, they are completely forgotten. Sometimes “miles per gallon” is mentioned, and cars are rated in horsepower.

To summarize, the large industrial and governmental organizations function largely in metric units. The small and medium enterprises will convert when their competitors in the United States do so. In general, a person’s acceptance of metric is in direct proportion to his level of education, and the news media reflect this. Complete acceptance of the metric system by the general public will probably occur only after the older generations have died off.

UK Metrication History and Status

by Chris Keenan, Special UK Correspondent to the USMA

The metric system was first legalized for scientific use in 1864. Then in 1871 the House of Commons proposed to make metric the only legal system for all purposes, but the proposal was defeated by only five votes. It was not until 1897 that the metric system made legal for trade as well.

In 1947 Prime Minister Clement Attlee commissioned a study on the future use of metric units in the UK. A resulting 1950 report stated that the metric system was a superior measurement system, and would eventually become the norm, but that the UK should wait until the Commonwealth and North America converted, as these were our main trading partners. Business was unenthusiastic about the metric system for this reason.

The British Standards Institution produced a survey in 1963 which indicated a significant majority of industry favoured metrication. In 1965 the Government announced support for metricating the UK within 10 years. The Government established theMetrication Board in 1969, to help industry go metric in an orderly fashion. It was hoped to have the metric transition largely in place by 1975, but that provision could only be made for certain sectors of the economy. In 1980 the Conservative government came to power, with little enthusiasm for metrication or legislation, and it dissolved the Metrication Board, but by 1980 many sectors of industry had already gone metric.

In the following decade, little progress was made, and it was left to European Union (EU) Directives on Weights and Measures in 1989 and 1991, which declared the metric system as the official measurement system of all member countries, to force further action on the UK. Their main effects of the EU Directives were to mandate the use of metric units for all pre-packed goods by the end of 1994, and for bulk goods to be priced in terms of metric units by the end of 1999. The government kept delaying the legislation, so the law actually came into force in October 1995. The government also interprets the requirements liberally, so that non-metric quantities are still legal, so long as their metric equivalent appears first on the label (e.g. pints of milk, ground coffee in pound packs). The transition to metric sales of loose products is already taking place. Supermarket chains are in the process of converting their scales to show prices per kg, and weight in kg. Most expect to be changed before winter, well in advance of the January deadline. Street market traders may prove more problematic.

The one significant aspect of measurement on which the UK and Ireland negotiated a derogation for which no date has yet been set is in the use of miles, yards, feet and inches for road traffic purposes. This has been misrepresented by some as a permanent licence to continue the use of imperial units in this field, or even as a bar to the use of metric units. The truth is that the UK has simply not set a date for conversion (despite the obligation to do so, albeit with no deadline set for it), and that there is no reason for UK legislation to be amended to permit more widespread use of metric units. Despite Ireland’s similar derogation, they have now largely completed the conversion of distance signs, and plan to convert speed limit signs during 2004. In the UK, speedometers have given dual English-metric units for many years, and metric units are increasingly seen on signs indicating distances in metres. In addition, certain commercial vehicles where the drivers are governed by EU regulations on working hours and distances travelled (e.g. coaches and trucks) have speedometers which show km/h in large figures, with mph in smaller figures; their odometers register km only. Also, the conversion of Ireland’s road signs to metric must put further pressure on the UK to eventually finish their metric transition.

Comments on Metrication in Ireland

by Tom Wade, Network Manager, EuroKom, Dublin, Ireland

Ireland, like the U.S., inherited the Imperial System of measurement from Britain, and these units continued to be used after Irish independence. It is principally due to Irish membership in the European Union (EU) that metric units were introduced. Progress towards metrication is mixed. Legally, Ireland is quite advanced, but there is still widespread (though decreasing) use of Imperial units in everyday conversation. Most older people cannot visualize metric quantities easily. Although most people don’t feel strongly either way, many find it easier to keep with what they are familiar. For example, most people know their height in feet and inches rather than meters, and their weight in stones (1 stone = 14 pounds) and pounds rather than kilograms. The Irish people tend not to have an emotional attachment to the old units as they do in the U.S. or the UK. Most people have a positive attitude toward the European Union, which is seen as the main reason behind metrication. Overall, the position is that metric units tend to be used in ‘official’ communications, whereas everyday speech tends to use Imperial units. The main hope is that as the percentage of metric educated people increases, this will change.

The metric system is the only system taught in schools. Beginning in 1970, textbooks were changed to metric. Up to five years ago Imperial units, dominated in the media (both TV and print), but in the last five years the use of metric units has caught up, and has overtaken Imperial. The presence of Imperial units in the media means that people leave school knowing the metric system, but are subjected to Imperial units thereafter. Goods in shops are labeled in metric units, but often with Imperial equivalents. All distance indications on road signs are in kilometers or meters. Road speed signs were changed to metric in January 2005 (see below). The Celsius temperature scale is almost universal, and weather reports now quote wind speed in kilometers per hour.

The principal legal instrument of metrication in Ireland is SI 255-1992 (note – the SI refers to Statutory Instrument, which is the mechanism by which European Council decisions are given legal effect in this country). This SI was introduced to give effect toEuropean Directive 89/617/EEC, which is also binding on other member states. SI 255 formally adopted the metric system as the official system of measurement, and specified the use of these units in trade, as well as the phasing out of Imperial units. The regulations came into effect on 7 September 1992. However, was not any attempt by the government to provide a metric campaign in the media prior to the road speed sign campaign last year.

Goods must be labeled and sold using ‘authorized’ (i.e. approved metric) units after 31 December 1993 (with certain exemptions). Units which have ceased to be ‘authorized’ (i.e. Imperial units) may be used as ‘supplementary indication’ until 31 December 1999, provided such supplementary indication is accompanied by an authorized unit. The clear implication here is that Imperial units should not appear at all after that date. Where both authorized and supplementary information is given, the former must predominate, and the latter must be expressed in characters no larger than those of the corresponding authorized unit.

A person shall not on or after the 1st day of January 1993, offer or supply for sale, rental or lease any weighing instruments, for retail use, other than instruments indicating only in metric units. Household items such as bathroom scales and measuring tapes are nearly always dual units. The use of units such as pint, fluid in alcoholic or soft drinks sold in returnable containers is permitted until 31 December 1998 (but has all but disappeared, apart from draught beer sold in bars). Presumably this was so as not to make all those glass bottles obsolete overnight. Drinks sold in plastic or aluminum containers are in liters or milliliters. No final date was set for the phasing out of the use of the pint in dispensing draught beer, or the use of Troy ounces in precious metal transactions.

A significant step was taken in January 2005, when the road speed signs were changed from miles per hour to kilometers per hour. Before this, distance signs were metric, but speed signs were in Imperial. Many journalists, experts and members of the public had drawn attention to this anomaly in articles and letters to the press. The deadline for change had been set for 1995, but had been postponed many times, more out of a lack of desire to spend the money than any opposition.

This changed because of two factors. Responsibility for road signage was moved from the Department of Environment and Local Government to the Department of Transport, (the latter made the regulations for car instrumentation, so any change before this had fallen between the two). The other was that a growing awareness of the high accident rate on Irish roads led to a move to increase enforcement, including the introduction of penalty points (which would see persistent offenders lose their licenses). This also prompted an examination into the suitability of the actual limits, which resulted in a recommendation to change many of them, and increase the frequency of speed signs. The Department of Transport decided to combine this with the changeover to metric signs, and a deadline of Dec 31st 2004 was set.

The limits were converted as follows:

- Motorway: Speed increased from 70 MPH (112 km/h) to 120 km/h (75 MPH)

- National Primary Road: Speed increased from 60 MPH (96 km/h) to 100 km/h (60 MPH)

- Default limit: Decreased from 60 MPH (96 km/h) to 80 km/h (50 MPH)

- Built up area 1: Decreased from 40 MPH (64 km/h) to 60 km/h (38 MPH)

- Built up area 2: Increased from 30 MPH (48 km/h) to 50 km/h (32 MPH)

- New limit for schools and traffic calming area: 30 km/h (19 MPH)

A publicity campaign was run on TV and the newspapers, and every house in the country received a brochure about the new limits. The only negative criticism that was received was in relation to some of the decisions as to whether certain roads needed to have their limits increased or decreased. There was almost universal approval of the decision to go metric.

Many car manufacturers changed their instrumentation in advance of the deadline. Since January 2005 all new cars sold in Ireland use metric instrumentation. These are the same instrumentation units used on the European mainland: they show speed only in km/h and distance (odometer) in km; there are no miles or miles per hour on these instruments.

The changeover deadline was extended to 2006-01-20 because of scheduling problems with the legislation (it missed the summer recess because another more controversial bill took up more time), but the signs were replaced over a three day period, and many additional signs were added. As was the experience in Canada and Australia, fears that confusion might lead to an increased accident rate were completely unfounded.

This changeover was a particularly significant and visible step in the progress of metrication. After the changeover, there was a noticeable increase in the prevalence of metric units used in the media. The weather forecasts also changed from MPH to km/h in reporting wind speed, and the use of metric units in conversation has increased.

Metrication of Australia

by Joseph B. Reid, President Emeritus, Canadian Metric Association

In April 1967 The Australian Senate appointed an all-party Select Committee “to inquire into … the practicability of the early adoption of the metric system”. The Committee held meetings in all capital cities, including 28 public meetings and 39 deliberative meetings. Submissions to the Committee overwhelmingly supported an early change to the sole use of the metric system.

In January 1970 the Prime Minister announced the decision to change and the Metric Conversion Act was assented to on 12 June 1970. In the same month the Metric Conversion Board was set up. The Board assembled 160 committees, sub-committees, and panels to analyze the problems likely to be encountered. At no stage was any industry or group asked to implement a program designed other than by fullest consultation and voluntary cooperation with the Board. The Act contained no penal clauses. Instead, the force of law would be achieved mainly by amendment of laws to incorporate metric measures.

The membership of all committees was nominated by the industry as experts with sufficient standing to make decisions without seeking prior approval from any other body. This technique ensured high competence, decisiveness, executive responsibility, and strong leadership of the industry.

The Board decided that metrication would be essentially a technical exercise and that people would best learn metric in their places of work or by adaptation to the changing material environment. Further, that the Board should limit public education to learning those metric units they would need to know in their jobs and professions. It was thought that the reasons for going metric would be difficult to explain to non-technical people and that attempts to do so could lead to unnecessary emotional argument and polarization of attitudes. This was the basis on which the Board decided to maintain a low key, and to concentrate on public education by involvement in day-to-day transactions in metric units rather than by more formal methods.

This decision to maintain a low profile now seems a little naive because metrication was a very significant cultural change in everyday life, and as a result opposition did develop.

It was agreed that conversion should take place in all directions simultaneously, rather than concentrate on a particular activity until completion. Thus conversion in the retail area, industry, government, weather reporting, and sports commentaries were all commenced more or less together. The Board also gave high priority to technical standards and codes of practice, and to amendments in legislation.

The Prime Minister and the head of the trade unions had been pals at Oxford University. That brought the unions on side. The Board also wooed the journalists: they were important in the reporting of events that have a broad public impact, without requiring action on the part of the public. The Australians are a very sports-loving people. One of the first activities to be metricated was horse racing, a very popular sport. That was easy because one furlong (220 yards) is very nearly 200 m.

Early all-pervasive changes helped greatly to expose the public to metric units. Such changes included tariffs (July 1972), horse racing (August 1972), and air temperature (September 1972). Metric description of athletics, soccer, golf, and cricket on television and radio, and in newspapers, served a useful educational purpose. Even the most dramatic changes such as speed limits to km/h only proved to be “non-events”. It was agreed that dual-marked signs would be potentially dangerous.

The conversion of retail food scales took place in 1974-75. It was found necessary to impose fines on retailers who did not convert.

A public opinion survey in December 1976 indicated that many still knew little of the metric system, and often less of the imperial system. They managed well, as always without needing to involve themselves with quantities, whether metric or imperial. This led the Board to conclude that any attempt to further “educate” the public would probably be ineffective and unnecessary.

A conference of Commonwealth and State Ministers in October 1977 agreed to withdraw the legality of non-metric units used in contractual agreements.

Adult education classes on the metric system failed to attract interest, which confirmed the Board‘s belief that such courses were unnecessary. It also confirmed the Board‘s belief that people do not perceive metric in systematic form but learn each unit and its application as an independent and unrelated piece of information. As a consequence the highly logical nature of the metric system or the unsystematic nature of the imperial system had very little meaning for the ordinary citizen. Re-education of ordinary people should therefore concentrate on providing a new set of metric benchmarks and avoid irrelevant references to the elegance of the metric system.

At the outset, wide-spread public resistance seemed possible, but it did not occur, despite the efforts of a small band of dedicated anti-metricationists. Even major changes, such as speed limits and metric shopping, were not traumatic. Metrication was never a political issue, and it was actively supported by the trade unions.

By May 1979 the following programs were completed:

- Education at all levels

- Gasoline sales

- Weather forecasts

- Building and construction

- About 30 of the 50 sporting codes

- Retail sales in most States

Some fields were static or slow moving, including:

- international aviation

- precision engineering

- real estate advertising

- advertising of goods described, but not sold, by measurement e.g. furniture, kitchen utensils.

The Metric Conversion Board spent a total of $5 955 000 (Australian) during its 11 years of operation, and the Commonwealth Government distributed a total of $10 000 000 to the States to assist them in the conversion process. No accounting has been made of the cost to the private sector. The Prices Justification Tribunal reported that metrication was not used to justify price increases.

Metrication in Australia

(from the foreword to an official report titled Metrication in Australia* that documents and provides a valuable historical record of the metrication process)

Metrication effectively began in Australia in 1966 with the successful conversion to decimal currency under the auspices of the Decimal Currency Board. The conversion of measurements – metrication – commenced subsequently in 1971 under the direction of the Metric Conversion Board and actively proceeded until the Board was disbanded in 1981. The process was a most significant event in Australia’s integration with the modernising world.

Metrication is still in its early stages in the USA which looks to Australia as an example and a model of how the process can be carried out. Because of the USA’s strong cultural influence upon us, Australia’s conversion can never be 100% until that nation has also converted.

One can’t help being impressed by the magnitude of the task, by how much thought, planning and effort went into bringing it about, and by how many members of the general community participated in it. The change affected all Australians in both their private and professional lives and has been recognised as one of the great reforms of our time.

* Wilks, K.J., 1992: Metrication in Australia, Department of Industry, Technology and Commerce (DITAC), Commonwealth of Australia, ISBN 0-644-24860-2, 86-p.

South Africa Metrication

(from an official government news release on 1977 September 15 in connection with the completion of metrication in South Africa)

On 1967 September 15 the Honorable Minister of Economic Affairs announced the appointment of a Metrication Advisory Board to plan and co-ordinate the change-over to the metric system in South Africa. One of the first decisions of the Board was to introduce the Systeme International d’Unites called the SI for short, which had just been developed at that time and had already been accepted in principle by many countries as the eventual metric system.

A Metrication Department was created within the framework of the South African Bureau of Standards to implement the decisions of the Advisory Board.

Not only the fact that the decade that has passed since 1967 September 15 suits the decimal character of the SI perfectly, but also the fact that the Republic has become a metric country within the originally planned transition period of ten years makes today’s date a fitting one. The success achieved is largely due to the good co-operations received from commerce, industry, agriculture, the professions and other organizations, all government bodies at the central, provincial and local level, and, above all, the ordinary citizen. Without this co-operation such a profound change affecting each and every one of us would not have been possible.

South Africa is widely acknowledged as a world leader in the field of metrication and in the application of the SI system. Many countries now in the process of changing over have studied the South African change-over and are following the same pattern to a large degree. With the USA as the last large non-metric country now engaged in changing over and the existing metric countries also replacing their systems with the SI, it is clear that the SI will soon be the only system of units used in the world.

South Africa is proud of the leading role it has played in this important matter.

Metrication in Jamaica

by Lennox Salmon, Metrication Department, Jamaica Bureau of Standards

The implementation of the metric conversion programme in Jamaica, which is still ongoing, has been fairly successful albeit uneven process to date. The broad public sector and larger privately owned enterprises to a large extent have converted to the use of the metric units. However, the conversion process in the relatively large small business, and traditional domestic agricultural sectors has proven to be an essentially long-term task which gains are incremental in nature.

In 1977, the Office of the Metrication Board an agency established by the Jamaican Government to oversee the country’s conversion to the metric (SI) system of units was short-lived, faltering in 1978 due in part to a lack of political support. It however had introduced the teaching of metric units in schools’ curriculum and in the reporting of weather information. In 1990s with bipartisan support the metrication process, was resumed by the government with the establishment of a new Metrication Board to provide the direction, guidance and facilitation for the national conversion programme. In 1996 having achieved certain major objectives the Board was phased out and the responsibility for continuing the programme’s monitoring and implementation was passed to the Bureau of Standards.

Since the 1970s metric units were introduced into the curriculum of the primary and secondary school systems. The Common Entrance and CXC examinations syllabus use metric units. The Ministry of Education also supports a policy of procuring metric only textbooks for use in the school system. The non-formal sector involving vocational, adult literacy and retraining facilities were also being transformed.

In sports the conversion of the popular horse racing industry has almost been completed.

Petroleum products e.g. gasoline pump sales have been in litres and cooking gas in kilograms since the 1990s. Road signage, although still in transition, have been significantly converted islandwide. Distance signs are indicated in kilometres and speed limit signs in kilometres per hour. Newly installed and replacement water meters are of the metric type. At the ports and airports wharfage and cargo rates are based on metric units, as are police, weather and other public sector agencies’ reports and statistics. Government procurement documentation e.g. for post office services, and construction industry tenders, are also metric.

Most locally packaged goods and export commodities, traditional and non-traditional, are labelled in metric units, although USA labelling regulations pose a constraint with their requirement for the use of dual units on goods exported to that country.

Large producers of staple foods e.g. flour, rice, salt, sugar, chicken and other meats, supply products in metric units. A main objective of the Bureau of Standards, and a targetted area of work of its Metrication Department, is to have outlets supplying everyday breakbulk items trade in metric units. While not yet a majority, large and medium sized wholesale and retail outlets including supermarkets and fabric stores, have converted islandwide, particularly in the capital Kingston and adjoining urban centres.

The metrication policy has been supported by legislation e.g. a Weights and Measures ‘Conversion of Units of Measurement Order, 1998’ has been declared by the Minister of Commerce. This requires all industry, with a temporary exemption for trade in the traditional markets, to convert to metric units. The Weights and Measures ‘Prohibition of non-metric measurement devices for trade Regulations, 1998’ is intended to prevent the importation of non-metric measuring devices into the country.

Although there is still wide usage of imperial units in everyday conversation and even some resistance of the use of metric units amongst older folks, the metric conversion programme to date has gained credibility amongst stakeholders based on – the sustained implementation effort since 1991, and the Jamaican government’s public support for the policy e.g. its allocation responsibility for the programme’s completion to its leading standards agency, as well as the enactment of metric legislation. The prospects for carrying the process to its completion in the new millenium are therefore good.

Japanese Metric Changeover

by Joseph B. Reid, President Emeritus, Canadian Metric Association

Japan ratified the Convention du Mtre in 1886, and in 1890 Japan received the prototype metre and kilogram from the International Bureau of Weights and Measures.

In a law of 1891, which came into effect in 1893, the traditional units “shaku” and “kan” were taken as the fundamental units of length and mass. At the same time, the use of the metric system was approved and the conversion factors between the systems were fixed.

In 1909 the units of the inch-pound system were also adopted as legal. Japan had thus three legally approved measuring systems.

A bill making the metric system the unique system was passed by the Japanese Diet in March 1921 and promulgated in April. The date of enforcement of this law was fixed by the Imperial Ordinance of 1 July 1924. But the Ordinance also permitted the use of other units as a transitional measure.

The changeover to the metric system was to take place in two stages. In the first stage government offices, public services, and other leading industries were to convert in ten years. In the second decade all the other activities and enterprises were to convert. The state primary school textbooks were converted to metric in 1925.

The change went rather smoothly at the beginning, but as the second decade approached opposition became furious beyond all reason. The opponents of the metric system believed that the adoption of a foreign measuring system would have a bad influence on national sentiment, cause dislocations in public life, needless expense to the nation, prove disadvantageous to foreign trade, and hurt the national language and culture. In 1933 the government postponed the date of conversion of the first stage by five years, and the date of the second stage by ten years.

After this postponement opposition to the metric system became stronger, and a second postponement was announced. An Imperial Ordinance in 1939 allowed shaku-kan to be used indefinitely in special cases.

After the war due to the presence of occupation armies, sale of gasoline changed from litres to gallons, cloth from metres to yards. Again, Japan was using three systems. Fortunately, the occupation armies believed that it was reasonable to adopt the metric system.

A new “Measurement Law” was passed by the Diet in 1951, and was promulgated in June and enforced on 1 March 1952. It allowed the use of shaku-kan and inch-pound systems until 31 December 1958, the same date set by the old law after two postponements.

To prevent the re-occurrence of opposition to metrication, a Metric System Promotion Committee was organized. This committee was not an official one, but was composed of national and local government officials, scholars, members of the Japan Weights and Measures Association, and other representatives from private organizations.

The conversion campaign used the press, radio, television, and a shower of pamphlets. Consumer good sales were converted gradually, one after the other.

At the time of resumption of the metric campaign in 1956, the percentages of adoption of the metric system were: in electricity, gas, and water supply 95%; in chemical industry 90%; in metal working 80%; machine industry 70%; textile industry 60%; and in other industries 60%.

In 1958 the Diet passed the “Metric Unit Law to Coordinate Metric Revisions to Other Laws” which changed the non-metric units used in other laws and regulations to metric ones. The biggest job in this regard was the registration lists of lands and buildings. The rewriting started in 1960 and was completed by March 1969.

A letter of 4 December 1981 from the Japanese Standards Association stated: “the metric system in Japan has been completely adopted … However, the capacity of “sake” bottle and dimensions of construction of Japanese style houses have not been altered. In case of difficult or poor economical situations, Japan has adopted to express only in metric system, but not change the actual size thereof. For instance, the “sake” bottle has usually 1.8 litre in capacity that is equal to 1 “shoh”.”

Metrication in New Zealand

by Joseph B. Reid, President Emeritus, Canadian Metric Association

In July 1965, the New Zealand Standards Institute compiled a report on the consequences of the British decision to go metric. In 1966 the Standards Association (replacing the Standards Institute) set up a Metric Advisory Committee which produced a report in 1967 that stated that the adoption of the metric system was inevitable. The Government then appointed a Working Committee and, in February 1969, appointed a Metric Advisory Board with Ian D. Stevenson, a wise old man, as Chairman. TheBoard set up 14 Sector Committees, and under them, 24 Divisional Committees. There were also a number of Industrial Committees with liaison to the Board.

In order to give metrication a human face, Stevenson found a baby girl whose parents agreed to cooperate. In press releases the child was named Miss Metric. News and pictures of her progress were intermingled with press releases about the progress of metrication.

The New Zealand metric symbol, which can be seen on the USMA Website (this page), was introduced in March 1971.

By the end of 1972 the sale of such items as wool and milk, the temperature scale, and road signs had been metricated. Opinion in the news media showed a good level of interest and opposition had been on points of detail only. Only a few letters voiced outright opposition to the changeover. News on metrication and press comment was generally well informed and fair. Six A3-size posters were produced and 200 000 copies of A4-size memos were distributed. More than 20 lecturers were ready to tour the country. A ten-minute film for theatrical distribution was being prepared. Companies such as the Commercial Bank of Australia and Woolworths prepared displays. The Board produced displays for shopping malls. Give-away items included calendars, cardboard cubic decimetres, 150 mm rulers, and a chart of metric information. Athletics, cycling, volleyball, roller skating, and ice skating were completely metric.

In August 1974 the Board reported that there were over 300 people in its planning committees, and that it had 74 registered speakers on metrication available. It listed 33 industries and activities that had been converted.

By July 1975 the Metric Advisory Board had eight pamphlets, fifteen A3-size posters, and five A6-size cards. They also had various industry-oriented circulars, guides, and booklets.

On 5 May 1976 the Minister of Trade and Industry and the Minister of Labour issued a press release that said that building and construction, transportation, and a wide range of manufacturing and processing industries had substantially completed the changeover, and all other industries were well on the way. The Government would ensure that the changeover was made thoroughly and well by outlawing the old system of measurements as early as it could efficiently do so.

In December 1976 Parliament passed the Weights and Measures Amendment Act, which established two deadlines:

31 March 1977: To cease verification of new non-metric weighing or measuring appliances used in trading, to require that all textile products and floor coverings sold by retail by length or area be in metres, and that all pricing and advertising be in metric.

30 September 1977: To require metric only retail pricing in a retail establishment where the weighing or measuring appliances are metric, or where prepackaged goods show the contents in metric measure. Otherwise, where weighing or measuring not yet converted to metric, pricing to be dual metric/imperial, with no greater prominence to the imperial. To require that all advertising for retail sale or purchase express quantities in metric units and prices per metric quantity. That imperial units not be allowed in advertising. To cease annual verification of existing non-metric weighing appliances.

Metrication in India

by Sujay Rao Mandavilli

India’s successful metrication can be used as a special case study in view of the fact that at the time of metrication of the Indian economy, hardly 30% of the population could read or write. India’s metrication efforts, especially its big bang approach are widely perceived to have been successful and have been used as a role model in many developing countries. Developing countries have certain special characteristics that either aid or impede metrication and set them apart from developed countries. India’s experiences with the introduction of the metric system are probably similar to the experiences of most other developing countries.

Special challenges generally faced by developing countries in metricating their economies are as follows:

- Low level of education – Thus the potential reach of metric education and awareness programs is limited.

- Primitive infrastructure – This means that parts of the country tend to be isolated both geographically and culturally

In spite of all this, the metric system has percolated to the remotest of villages in India and subsequent to the banning of Imperial and native weights and measures all Indians think, breathe, and even dream metric day in and day out.

Advantages that developing countries have had with respect to metrication over many developed countries are as follows:

- No emotional attachment to English units: People seldom have an emotional attachment to English units (or even metric units for that matter) in developing countries. It is therefore generally a logical decision between two alien systems. Developing countries generally have no cultural preferences in the areas of science and technology. They tend to take what is best from developed countries.

- Anti-colonial stance: An anti-colonial stance in many developing countries helped popularize the metric system.

- Decimal cultures: Many Asian cultures prefer decimals to fractions. (After all the Decimal system originated in Asia.)

- Low public awareness was a blessing in disguise because this pre-empted any possible resistance. Less awareness meant that people generally did as they were told to by their governments.

- Early metrication: The advantage in developing countries was that metrication was initiated before the industrialization process began and when life was infinitely less complicated.

The history of metrication in India is as follows:

Older measuring systems in India: Prior to the introduction of the metric system in India in 1956, both English and native measures were used. This naturally led to chaos and confusion. The low level of literacy did not help, and to add to the chaos, different regions of the country had different measuring systems, or worse still, different interpretations of the same system. The following were the most common native measures used before the introduction of the metric system:

- 1 tola = 11.66 g

- 1 seer = 80 tolas = 932 g

- 1 maund = 40 seers = 37.29 kg

In 1956 the Government of India fixed the value of the seer at 0.9331 kg exactly. Similar native measures also existed to describe length and volume. Prior to 1956 knowledge of the metric system was virtually non-existent in India. A notable use of metric in India before 1956 was however in the railways. One of the three railway systems in India during the British period was known as the “meter gauge railway” owing to the width of its track – developed in the 1880s by the British, this essentially reflected the new-found interest in the metric system in England at that time.

1956 – The Government of India announces metrication: In 1956 the Government of India enacted the Standards of Weights and Measures Act in an attempt to bring order out of chaos and to help the nations fledging industry exchange ideas with its trade partners more easily. The objective of this Act was to declare all non-metric measures illegal by 1960.

Currency metrication – The first step: The first step undertaken was to reform the country’s weird currency system. In September 1955 the Indian Coinage Act was amended to adopt a metric system of coinage. At that time one Indian rupee consisted of 16 annas. Each anna consisted of 4 pice and each pice consisted of 3 pies. In effect one rupee consisted of 192 pies. This probably had something to do with British influence, as available evidence suggests that currency systems in use in India prior to the advent of British rule in India were different. The Act came into force with effective 1 April 1957. The rupee remained unchanged in value and nomenclature. It, however, was now divided into 100 paisa instead of 16 annas or 64 pice. For public recognition, the new decimal paisa was termed ‘naya paisa’ (or new paisa) till 1 June 1964 when the term ‘naya’ was dropped.

Phase out of non-metric weights and measures – The next step: The metric system was progressively introduced in various fields in the country from 1 October 1960. On that date the use of metric weights in trade became compulsory in selected areas covering over 20% of the population of India. The use of metric weights over the entire country was allowed from 1 April 1960 and became compulsory throughout the country from 1 April 1962. Metric measures denoting capacity were introduced at the same time. By 1962 metric weights were being used in transactions involving the purchase of raw materials or sale of products of many major industries like cotton textiles, soap, chemicals, cement, iron and steel, etc. By this date the metric system was also in use in the distribution of petroleum products throughout the country. Metric managed to conquer the kitchen soon enough, with all kitchen implements and cookbooks in English, Hindi, and other Indian languages converted to metric by the mid-1960s.

Government departments: The Indian railways in their commercial branches changed over to metric from 1 April 1960. The customs and excise departments changed over from 1 October 1960 and the posts and telegraphs department changed over from 1961. Most other government departments followed suit.

Education: In 1961 a conference was held at New Delhi to discuss the metrication of the education system. This was attended by principals of technical colleges and institutions and a program of changeover in engineering and technical education was chalked out. In accordance with this announcement, the full adoption of metric system in teaching began in the first and second year classes from the academic session of 1962-63 and in 1963-64 in the third and fourth year classes, followed by the introduction in the fifth and final year classes in 1964-65. From then on the inch-pound system was taught only as supplementary to the metric system. School curricula were similarly revised and all subjects were predominantly taught using metric system. By the early 1970s the Inch-pound system was largely discontinued from most educational systems in the country.

Transportation and road signs: All road signs were metricated by the mid-1960s when there were few motor vehicles in India – less than half a million vehicles then against over 40 million now. Speedometers and odometers had to change to kilometers. Nowadays nobody remembers miles anymore – it is viewed as an archaic measurement.

Fuel efficiency is measured in kilometers per liter and not liters per 100 kilometers. (10 kilometers per liter is reasonable for a medium-sized sedan, 20 kilometers per liter is pretty decent for a small car under 1 liter, and any vehicle that returns less than 10 kilometers per liter is a gas guzzler.) A Toyota Corolla, for example returns around 10 km/L, a tiny 0.8 L car returns around 20 km/L, while the most luxurious car sold in India today, the 6.8 L Bentley Arnage, returns just 4 km/L. It’s so simple if you get used to it!

Tire pressure is measured in kilograms per square centimeter (pounds per square inch only in some very old gauges) and tread sizes are in millimeters, while tire rim diameters are still measured in inches, as is common throughout the world.

While road lengths are in meters and kilometers, road widths are popularly measured in feet! (In our land of terrible roads – people take great pride in mentioning the fact that their street is 100 feet wide, for example – sounds very dramatic. Sometimes a 100 foot wide road just refers to a broad street.) However official documents use meters.

Weather: Since the 1980s most if not all weather reports have been metricated. Temperature is almost always in degrees Celsius and rainfall is measured in centimeters and millimeters. However body temperature is still sometimes measured in degrees Fahrenheit. (This is probably because 102 degrees Fahrenheit sounds more dramatic than 39 degrees Celsius.)

Time: The Gregorian calendar is followed in the country for all commercial purposes using the day-month-year format. However native calendars are occasionally used for religious purposes.

The number system: India is probably out of step with the rest of the world in one respect: “Lakhs” and “crores” are more commonly used than millions and billions even in the English press. One lakh is one-tenth of a million while one crore is 10 million. While Pakistan is gradually phasing out non-standard numbering systems, lakhs and crores continue to be widely used today in India even today.

Body height and temperature: While body mass is always in measured kilograms, body height is often measured in feet and inches although centimeters are being increasingly used in many documents.

Industry: Almost all types of industry in India operate exclusively in metric units. However a handful of industries like the construction and the real estate industry still use both the metric and the Imperial system probably because of their continued reliance on designs originating in the U.S. These will probably complete their conversion to metric when the U.S. does.

Current status of Imperial units:

- Imperial units that are long forgotten: Ounces, gallons, miles, pounds, pints, and quarts (only metric equivalents are used and it is likely that people born after 1980 might not even have heard of them!)

- Imperial units used along with metric equivalents: Inches, feet, yards (square yards for area), degrees Fahrenheit (Both metric and Imperial units are popular)

- Imperial units more popular: Acres (hectares are generally used only in government documents)

Indian experiment successfully followed in south Asia: India was one of the first countries in the developing world to metricate its economy. By 2006 India will have completed half a century of metrication. Many countries in Asia and Africa have since followed India’s model. While the Indian economy continued to languish till the 1990s despite metrication (for an entirely different set of reasons) metrication has indeed help boost the country’s exports and integrate it more easily with the world economy.

The phasing out of the remaining non-metric units in India will probably accelerate when the U.S., one of India’s largest trading partners, finishes metricating its economy. When the remaining non-metric countries adopt the metric system, Imperial units will slowly fade away from public consciousness and the conquest of the SI as the world’s only language of measurement will be complete.

References:

- Republic India Coinage from RBI Monetary Museum, http://www.rbi.org.in/currency/museum/c-rep.html

- The Standards of Weights and Measures Act, http://www.indiaagronet.com/indiaagronet/AGRI_LAW/CONTENTS/The%20Standards.htm