Here are some incidents that involved confusion between units or systems of measurement.

They vary in significance and seriousness, but in each case, the problem would have been avoided had there not been a mixture of measurement systems. Using the metric system doesn’t guarantee that such problems will never occur, of course, but the metric system is so much simpler than other systems that errors are much less likely. And using dual units further increases the chances of errors over using a single system of measurement. As long as inch-pound units survive in an otherwise metric world, these types of conversion problems are likely to continue.

Contents

- Expensive rice

- Escape of the 250-kilogram tortoise

- Winning long jump record lost

- Loss of Mars Climate Orbiter

- Roller coaster derailment at Tokyo Disneyland’s Space Mountain

- Gimli Glider: Boeing 767 emergency landing

- Olympic triple jump loss

- Korean Air MD-11 crash

- Medication dose errors

Expensive rice

An American company sold a shipment of wild rice to a Japanese customer, quoting a price of 39¢ a pound. But the customer thought the quote was for 39¢ a kilogram, so the actual price was more than twice what the customer expected.

In the interest of maintaining a long-term business relationship after the misunderstanding, the seller discounted the rice to his cost, and ended up making no money on the deal. “[The customer] had to explain to her boss. Everyone was embarrassed. We both ended up losing money on the deal.”

(See the 6 July 2001 San Francisco Business Times story, Manufacturers, exporters think metric.)

Escape of the 250-kilogram tortoise

What happened

In February 2001, the Los Angeles Zoo lent Clarence, a 250-kilogram, 75-year-old Galapagos tortoise, to the Exotic Animal Training and Management Program at Moorpark College in Moorpark CA.

The first night in his new home, Clarence wrecked it: “He just pushed one of the fence poles right over,” said Moorpark’s Chuck Brinkman, quoted in a 9 February 2001 Los Angeles Times story.

Why it happened

The L.A. Zoo warned that Clarence was big, and needed an enclosure for an animal that weighs in at about 250, so that’s what the college built.

Unfortunately, they thought the zoo meant 250 pounds, so the enclosure wasn’t adequate for holding a 250-kilogram beast.

Winning long jump record lost

What happened

University of Houston sophomore track star Carol Lewis made a record-breaking long jump at the NCAA Men’s and Women’s Indoor Track Championship, 11–12 March 1983 in Pontiac, MI.

However, her jump did not qualify as an official record.

Why it happened

To be considered as official records, college sports track and field measurements must be metric. However, officials hosting the games refused to use metric tapes. As a result, the non-metric measurements don’t qualify as official records. For record-setting purposes, measurements cannot be converted to metric after the event.

[Source: American National Metric Council Metric Reporter, May 1983.]

Loss of Mars Climate Orbiter

What happened

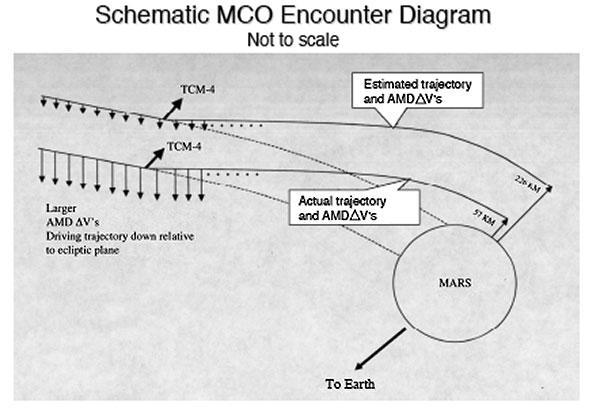

Mars Climate Orbiter (MCO) was launched on 11 December 1998 on a mission to orbit Mars as the first interplanetary weather satellite and to provide a communications relay for another spacecraft, the Mars Polar Lander. MCO was lost on 23 September 1999 when it failed to enter an orbit around Mars, instead crashing into the planet, destroying the $125 million craft, part of a $328 million mission.

Why it happened

The root cause of the failure was a computer program that was supposed to provide its output in newton seconds (N·s) but instead provided pound-force seconds (lbf·s). From the mishap investigation report:

Angular momentum management is required to keep the spacecraft’s reaction wheels (or flywheels) within their linear (unsaturated) range. This is accomplished through thruster firings using a procedure called Angular Momentum Desaturation (AMD). When an AMD event occurs, relevant spacecraft data is telemetered to the ground, processed by the SM_FORCES (“small forces”) software, and placed into a file called the Angular Momentum Desaturation (AMD) file.

The JPL operations navigation team used data derived from the Angular Momentum Desaturation (AMD) file to model the forces on the spacecraft resulting from these specific thruster firings. Modeling of these small forces is critical for accurately determining the spacecraft’s trajectory. Immediately after the thruster firing, the velocity change (ΔV) is computed using an impulse bit and thruster firing time for each of the thrusters. The impulse bit models the thruster performance provided by the thruster manufacturer. The calculation of the thruster performance is carried out both on-board the spacecraft and on ground support system computers. Mismodeling only occurred in the ground software.

The Software Interface Specification (SIS), used to define the format of the AMD file, specifies the units associated with the impulse bit to be newton seconds (N·s). Newton seconds are the proper units for impulse (force × time) for metric units. The AMD software installed on the spacecraft used metric units for the computation and was correct. In the case of the ground software, the impulse bit reported to the AMD file was in English units of pounds (force) seconds (lbf·s) rather than the metric units specified. Subsequent processing of the impulse bit values from the AMD file by the navigation software underestimated the effect of the thruster firings on the spacecraft trajectory by a factor of 4.45 (1 lbf·s = 4.45 N·s).

As a result of the incorrectly computed trajectory, the spacecraft’s initial periapsis (low-point in the Martian orbit) was only 57 km; the minimum survivable periapsis was 80 km.

Wouldn’t an error that large — a factor of 4.45 — have been noticeable? Yes, as it turns out: “Almost immediately (within a week) it became apparent that the files contained anomalous data that was indicating underestimation of the trajectory perturbations due to desaturation events.” However, for a variety of reasons, the source of the inconsistencies wasn’t determined until after the loss of the spacecraft.

For the details, read the Mars Climate Orbiter Mishap Investigation Board Phase I Report, issued on 10 November 1999.

(The other half of the mission — Mars Polar Lander — also crashed into the surface of Mars due to a computer program bug, but that incident was not related to measurement.)

Roller coaster derailment at Tokyo Disneyland’s Space Mountain

What happened

On 5 December 2003, the Space Mountain roller coaster at Tokyo Disneyland derailed when an axle broke just before the end of the ride; there were no injuries.

Why it happened

According to a 21 January 2004 report from Oriental Land Co., which built and operates Tokyo Disneyland, the diameter of the broken axle was found to be smaller than its design specification. As a result, the gap between the axle and its bearing, which should have been about 0.2 mm, was actually over 1 mm, resulting in excessive play that caused more vibration than normal, eventually causing the axle to break.

The broken axle was one of 30 axles received in October 2002, all of which were found to be thinner than the design specification as a result of an error when they were ordered in August 2002.

That error arose from improperly maintaining the design drawings. In September 1995, the design specifications for the axle bearing had been changed to metric units, and the specification for the axles was therefore changed as well. As a result, there were two sets of design drawings. In August 2002, the old drawings were mistakenly used to order 44.14 mm axles instead of the correct, 45 mm parts.

The company confirmed that other orders for axles used the correct dimensions.

Gimli Glider: Boeing 767 emergency landing

What happened

On 23 July 1983, Air Canada flight 143, a Boeing 767 flying from Montreal to Edmonton via Ottawa, ran out of fuel about an hour into its flight. At an altitude of 41,000 feet the crew received its first indication of low fuel pressure in one fuel pump, and a few seconds later, in the other fuel pump. (Aircraft are assigned altitudes that are multiples of 1,000 feet. 41,000 ft is about 12,500 m.)

An initial decision to divert to Winnipeg had to be abandoned when both engines failed. Luckily, the first officer was aware of a decommissioned air force base in Gimli, Manitoba, about 20 kilometers away, and the captain was an experienced glider pilot; they managed to land the 767 on the runway — now a drag strip. The partially extended nose gear collapsed on landing, stopping the aircraft before it hit anyone on the ground. Two passengers suffered minor injuries using the emergency slides to evacuate the aircraft.

Why it happened

The aircraft’s fuel quantity indication system had begun malfunctioning three weeks before the incident. It failed completely the night before the flight. The mechanic investigating the failure was told that no spares were available, but he discovered that pulling a circuit breaker brought it back to life, so he left the breaker open, the flight was fueled, and it flew from Edmonton to Ottawa to Montreal without incident.

In Montreal, a maintenance worker was assigned to manually check the aircraft’s fuel levels, due to the problems with the fuel monitoring system. While waiting for the fuel truck, he decided to investigate the problem, although he had no training or authority to do so.

Curious about the open breaker, he closed it, causing the fuel gauges to again go blank. He left, and the crew, seeing the blank gauges, decided to resort to manually calculating the amount of fuel required for the trip back to Edmonton and on to Ottawa. (The problem was later determined to be a cold solder joint on an inductor combined with a design flaw that prevented the unit from switching to a backup.)

The maintenance workers performed a test that estimated that 7,682 liters of fuel were in the tank. They knew they needed 22,300 kilograms of fuel for the remaining flight, so the question was, How much fuel, in liters, should be pumped from the fuel truck into the aircraft? They were forced to resort to a manual calculation:

- They multiplied 7,682 L by 1.77, the density of the fuel provided by the refueling company on their documentation: The aircraft, according to their calculations, currently had 13,597 kg of fuel.

- Subtracting from 22,300 kg, they decided they needed to add 8,703 kg of fuel.

- Dividing by 1.77 — the same density used in the previous calculation — yields 4,916 L, which was pumped into the aircraft.

However, 1.77 was the density of the fuel in pounds per liter (lb/L), not kilograms per liter (kg/L); the correct figure for kg/L would have been 0.80. As a result, they ended up with less than half of the required amount of fuel on board. (The fuel’s density depends on characteristics of the fuel, so it’s not a constant, and the value must be taken from documentation accompanying the fuel.)

The ground crew didn’t notice the discrepancy because 1.77 was typical of numbers they’d seen before. They assumed the number was in kg/L, not realizing that this was the first aircraft in Air Canada’s fleet to measure fuel in kilograms; density figures on paperwork hadn’t yet been changed from lb/L. The refueler didn’t notice the discrepancy because he had no idea where the aircraft was headed, so he had no reason to question the relatively small amount of fuel the crew asked for.

In addition, fuel amounts hadn’t been calculated by hand since the days of three-man cockpit crews, where the flight engineer was responsible for checking the fuel load. That process was normally handled by computer on an aircraft like the 767. What if the computer wasn’t working? In 1983, that question hadn’t been adequately addressed.

On aircraft with a two-man crew, tasks formerly assigned to the flight engineer were either automated or assigned to ground staff, so theoretically the ground crew was responsible for ensuring adequate fuelling if the automation couldn’t handle it. But maintenance crews had never been trained on how to calculate fuel, so they assumed the flight crew would handle it. But the flight crew had never been trained in this process, either. Furthermore, Boeing documentation at the time was inconsistent as to whether the aircraft could safely fly with a malfunctioning fuel monitoring system.

Media coverage at the time pointed out that this was Air Canada’s “first aircraft to use metric measurements,” but that’s only partially true. Although it was the first to measure fuel mass in kilograms rather than pounds, fuel volumes were already metric, in liters.

Olympic triple jump loss

What happened

At the 2004 Olympics in Athens, triple jump champion Melvin Lister was eliminated in the qualifying round. Although he had jumped 17.75 m in Sacramento the previous month, his top jump was only 16.64 m in Athens.

Why it happened

A Kansas City Star article quoted Lister as saying, “Nobody told me they were only going to have metric out there. I couldn’t figure out what my mark was.” And from the 21 August 2004 Los Angeles Times:

Lister blamed his problems on trackside officials’ refusal to allow him to use his measuring tape, which measures distances in feet and inches and serves as a guidepost for him. He said he was told the tape “might hurt somebody” because of a spiked attachment and was told to use a metric tape, but he didn’t have one and couldn’t work with the metric tape organizers supplied.

“Nobody told me I need one,” he said. “Coming down, I need my running speed and to trust in my approach.”

Teammate Walter Davis, who advanced with a leap of 16.94 meters, scoffed at Lister’s excuse. “When you’re coming overseas, you’ve got to have a metric tape,” he said. “Mine is in feet and meters. You’ve got to come prepared.”

Korean Air MD-11 crash

What happened

On 15 April 1999, Korean Air flight 6316, an MD-11 freighter on a flight from Shanghai to Seoul, crashed shortly after takeoff from Shanghai Hongqiao Airport. The aircraft was destroyed, its three crew members and five persons on the ground were killed, and 37 on the ground were injured.

Why it happened

The flight was initially cleared to an altitude of 900 meters, then instructed to climb to 1,500 meters. After reaching about 1,400 meters, the crew erroneously concluded that they had misinterpreted the altitude. Having decided that they should be at 1,500 feet, rather than meters, they began a rapid descent.

During the process, they lost control of the aircraft and crashed.

Note that aircraft altitudes are in feet throughout the world, except for China, Mongolia, and the CIS (former Soviet states), which use meters.

Medication dose errors

What happened

In 2004, a baby was given 5 times the prescribed dose of Zantac Syrup, a medication for reducing stomach acid production, until a doctor pointed out the error a month later. Fortunately, the child was not injured, although doctors say there was a risk of seizure or stroke had the incorrect dosing continued.

Why it happened

The doctor prescribed a dose of 0.75 milliliter twice a day, but the pharmacist labeled the bottle, “Give 3/4 teaspoonful twice a day.” A teaspoon is about 4.9 mL.

Note that an additional source of error, given a prescription in teaspoons, is that consumers might use teaspoons from the silverware drawer instead of measuring spoons.

See “Pharmacy makes another potentially dangerous prescription mistake” from WFTV for more details.

Back to USMA home.

Copyright © 2006–2009 US Metric Association (USMA), Inc. All rights reserved.

Updated: 2009-01-05